In early 2001, investors were shaken. The dotcom bubble was bursting, with stocks in major tech companies such as Amazon and Apple losing trillions of dollars of value. The slide in shares was illustrated best in the tech-heavy NASDAQ index, which lost 70% between 2000 and 2002. However, in the midst of the poor performance of the tech sector, one company at least seemed to be doing well. energy and commodities giant Enron corporation, named America’s “most innovative company” by Fortune for six years running, appeared to be doing just fine. In the first quarter of 2001, it reported profits up over 20% up on the year before, beating analyst expectations owing to what CEO Jeff Skilling attributed to ‘transaction and volume growth’ in the wholesale business. Enron seemed to be a company on the up.

However, in mere months, everything changed. Revelations came to light of grossly exaggerated profits, hidden debts, webs of shell companies and overvalued assets, casting Enron in an entirely different light: Far from profitability, the company had been misrepresenting its’ income (or lack of it) to investors, managing to fool all major players in the world of business at the time. On December 1st, Enron filed for bankruptcy, its’ credit rating downgraded to junk status by several agencies, and with no prospect of paying off mountains of liabilities. Now-former CEOs Jeffrey Skilling and Kenneth Lay went on to be convicted on a total of 25 counts of securities fraud and wire fraud, with the name Enron now being synonymous with corporate dishonesty and deception. But how did Enron manage to become the seventh-largest company in America, whilst managing to convince pundits and analysts alike that, far from being fraudulent, Enron was actually pioneering a radical new business model? To understand this, we have to go back to the very beginning.

The Birth of Enron

The company known as ‘Enron’ was born out of a merger of two energy firms, Houston Natural Gas and InterNorth in 1985, seeking to take profit from the increased volatility in natural gas prices that arose in the 1980s as a result of deregulation of the sector. Houston Natural Gas CEO Kenneth Lay was appointed to lead the new company, and in 1988, the company decided to pivot: It would expand further into unregulated energy markets, starting off with building a power plant in the newly privatised British sector. At this point, Enron was still merely a conventional energy company with an ambitious expansion plan. However next year, a new world of possibilities was opened up, as Enron launched its’ first major innovation:

The Gas Bank

At this point, in 1989, Jeffrey Skilling was a consultant working with Enron, brainstorming new ways for the company to make money. Skilling proceeded to come up with an idea so radical and innovative that Lay not only took it on and implemented it, but invited Skilling to come on board and lead the project himself. The idea was a first of its’ kind: Rather than Enron as an energy company purchasing or extracting natural gas, then shipping or pumping it via pipeline to consumers, why not also act as a platform through which suppliers and wholesale buyers can conduct their own trading? And so, Enron launched its’ Energy bank: A platform on which Enron acted as a mediating platform for the sale of gas between two parties. Suppliers sold gas to the Gas Bank, and wholesale buyers purchased it, whilst Enron charged a commission fee for each transaction made. Additionally, transporting the gas from buyer to seller would be arranged by individual sellers – with this, Enron was no longer bound by its’ pipeline capacity when selling gas.

Although trading natural gas like any other commodity is commonplace today, in the early 1990s, this was a revolutionary idea that had never been tried before, with almost limitless potential. This kind of innovation would come to define Enron in the public eye – they seemingly found opportunities to make money at every turn, doing things that other energy companies hadn’t even thought of before. Their motto, ‘question everything’, reflected the innovative face that they presented to the public. And so, Jeff Skilling joined the Enron team, and the company.

Mark to Mirage Accounting

In the early 1990s, Enron capitalised on its’ gas trading innovations. It even became one of the first major traders in natural gas on the New York Mercantile Exchange, or NYMEX.

Enron’s next ‘big innovation’ came with another big innovator: Andy Fastow. Hired by the energy trading department of Enron, Fastow quickly rose through the ranks. There, he proposed the adoption of another radical concept aimed at innovating Enron’s cashflow, theoretically allowing Enron to more ‘accurately’ report earnings: Mark-to-Market accounting.

In ‘conventional’ accounting, companies report revenue and expenditures as they happen: For example, if Enron were to agree to sell $1 million worth of natural gas next quarter, that money would only be reported as a profit when it was paid to Enron by the buyer. However, under mark to market accounting, the idea was that companies should record their revenues based off of the money that they are going to earn, rather than the money that they actually earned. Therefore, if Enron’s energy trading department signed a deal to sell gas at some point in the future, they could list it as revenue earned the moment the deal was signed. Fastow pitched this as ‘improving the accuracy’ of revenue estimates, taking future revenue prospects into consideration. The idea took hold in Enron’s gas trading business, and in 1997, the SEC approved broader usage of mark-to-market accounting across all forms of trading, and Enron expanded its’ usage across the entire company.

However, the flaws of mark-to-market accounting are best illustrated by one case: The building of the Dabhol power plant in India. Enron signed a $2.8 billion contract to build a massive gas-fired power plant in India, the largest foreign investment project in the country at the time. As a result, Enron was able to ‘cushion’ its’ revenue stream with predicted profits from its’ assets in India before construction projects were even completed. However, Enron had severely overestimated Indian demand for electricity, as well as the logistical difficulties in a construction project of such a large scale. Therefore, the Dabhol project was repeatedly delayed, and even when it did open, Enron was forced to sell electricity at a heavy discount, continuously losing money. Despite this, as Enron believed that the plant was capable of profitability in the future, predicted earnings were added onto Enron’s earnings reports, making the company appear to be in much better financial shape than it actually was.

The Raptors

The Dabhol project was not the only venture Enron was losing money on. Through the 1990s, Enron had invested into a number of international projects in Brazil, Europe, China and the Philippines. Most of these projects were costing the company billions, and persistently failing to turn a profit. Although Enron used mark-to-mark accounting to effectively hide losses from investors, the fact remained that Enron was having to borrow large amounts of money to simply keep operations running – borrowing of a scale that would unnerve investors, and alert analysts if it came to light. Here we meet Andy Fastow again – with yet another big idea, but this one crossed the line from misrepresentation to fraud.

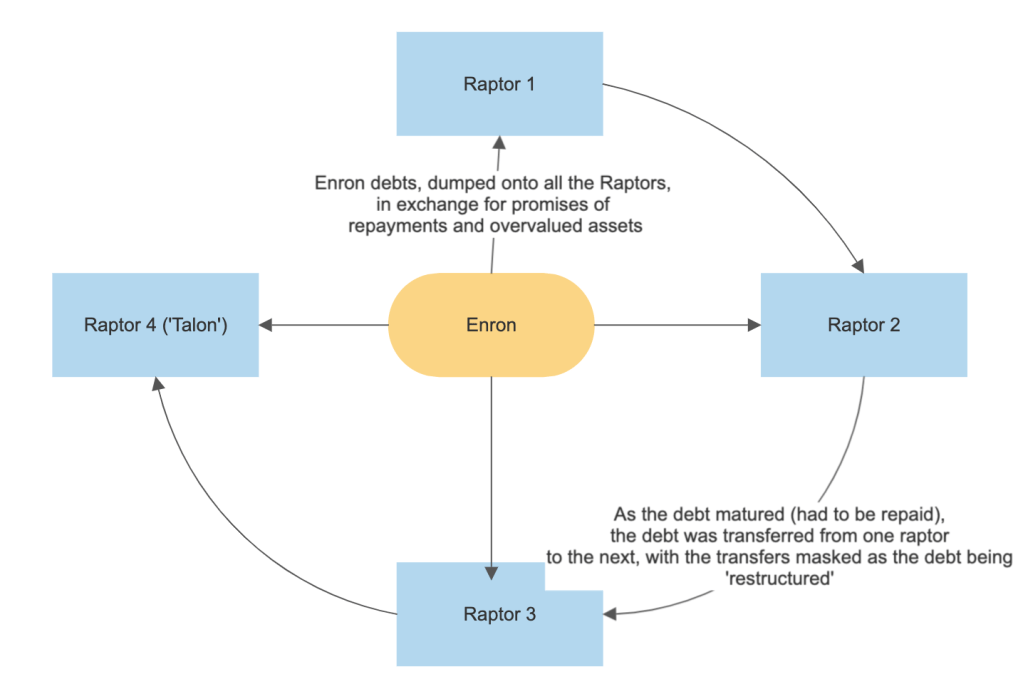

Fastow wanted to create nominally independent organisations, nicknamed the ‘Raptors’. Then, these Raptors would buy up Enron’s debt, hiding it from the general public. To legally declare the Raptors as independent whilst continuing to control them, some creative thinking was required. Fastow set up the raptors as ‘Special Purpose Entities’ (essentially, companies that existed to fulfil a narrow purpose), and invited reputable investors that were renowned throughout the finance world to become partners. These investment firms, whom Fastow had built up strong personal relations with over the years owing to Enron’s unblemished reputation and strong marketing, were willing to trust Enron, and as a result did not engage in serious attempts at due diligence – as they saw it, Enron were highly successful industry leaders offering them a chance to take part in an exciting new venture, why waste time verifying details and risk missing out? And so, Enron was able to hide debts from analysts, shuttling them into de facto shell companies.

Enron offloaded bonds onto the Raptors, giving the Raptors repayment options and overvalued assets ‘in exchange’ for the raptors ‘agreeing’ to take on the debts of Enron. When the debts matured in one Raptor, it simply transferred all of its’ debts onto the next Raptor, and the cycle repeated. from 1999 to 2001, the Raptors masked the poor financial state of Enron, creating the perception that the company was stable.

Blackouts and Arnold Schwarzenegger: Enron in California

Now that Enron had figured out a way to control its’ own debt and project an image of growing revenues to investors, executives banked on being able to ‘fake it ’til they made it’. All that remained was to start trying to make money somehow. And Enron saw a golden opportunity in the golden state: California. In 1992, Federal legislation had been pushed through that paved the way for individual states to deregulate their electricity markets, an opportunity California took in 1996, hoping it would spur innovation, modernisation and lower power prices. However, the energy traders at Enron saw California as not just a market, but a captive consumer base to be exploited for profit. Enron energy traders began mapping out the Western power grid, calculating the methods that could be used to pump up energy prices as much as possible. They soon devised the following model:

- During periods when the power grid was nearing capacity, Enron would deliberately overload power lines. Then, it would only agree to relieve the congestion (which it had created) for exorbitant fees.

- At other periods, when demand for power in California was low, Enron would funnel electricity out of the state across the shared power grid with the rest of the Western states, to sell at marginally higher prices out-of-state

- Enron continued this until demand outpaced supply in California: In other words, it continued pulling power out of California until there were power shortages, with the state being hit by rolling blackouts, and electricity prices in California skyrocketed

- Once the electricity prices reached exorbitant prices, Enron would then stop routing power out of California, selling more power to California and pocketing massive profits

At the same time, before pulling these tricks, Enron would engage in speculation on energy markets, cheaply purchasing contracts to buy electricity from outside of California ahead of time- essentially, Enron ‘bet’ that electricity prices would spike in California, then it would funnel power out of California, causing electricity prices to spike. Enron then was able to use its’ pre-existing contracts to buy electricity from other states cheaply, and sell it to California, where electricity prices were unnaturally high.

Governor Davis did try to remedy this. He repeatedly appealed to President George Bush and VP Dick Cheney to impose Federal price caps on California wholesale electricity prices, and to give him the authority to unilaterally renegotiate power contracts with energy providers, requests that were continually rejected by the Bush administration. This aligned neatly with Enron’s interests, all the more so considering that Enron had been the single largest donor to the Bush presidential campaign in 2000.

The people of California ultimately associated the blackouts of 2000-2001 with the incompetence of Davis, and so, in 2003, he failed to win re-election. His replacement: A Hollywood star turned politician, by the name of Arnold Schwarzenneger. And so, you could argue that it’s because of Enron that the Terminator found his way into politics.

The House of Cards begins to tumble

By early 2001, it was clear to Skilling, Lay and Fastow that even with its’ Californian ventures, Enron was far from profitable, and continuing to accrue debt. And yet, Enron was able to continue to overreport predicted earnings with seeming impunity, hiding ever-growing mountains of debt behind the Raptors. As long as it could keep its’ share price high, executives hoped Enron could keep the facade up for as long as was necessary. However, the house of cards began to tumble. In February, Fortune reporter Bethany Mclean asked newly-appointed CEO Jeff Skilling a simple question: How exactly did Enron make its’ money? Skilling was at a loss. He didn’t know how to respond – he couldn’t just admit that Enron hadn’t been profitable for years. So he promised to send Fastow and a team of accountants to ‘explain the business model’ of Enron. These accountants and Fastow spent hours going over records and transactions of Enron with Mclean, but something seemed amiss. Though she couldn’t prove Enron was engaging in fraudulent activities, her article, which came out in early March was simply titled ‘Is Enron Overpriced’? , focusing on the remarkably high price to earnings ratio of Enron shares. This began to deflate share prices, which had already been on a gentle downward trajectory in the wake of the dotcom bubble bursting, which had shaken investor confidence in ‘innovative’ firms like Enron. Skilling attempted to calm investors in a conference call, where he accidentally snapped, calling one who asked why Enron could not provide detailed balance sheets an ‘asshole’.

Now the markets were worried – it was one thing for a newspaper to publish a negative article, but the CEO of the seventh-largest company in America insulting investors was something else. People began to wonder if Enron was really as stable as it appeared to be. Despite recording profits in July 2001 which stood at an (inflated) all-time high, share prices had declined by over 30% in the previous 12 months. Next month, Skilling abruptly resigned his position as CEO of Enron, claiming it was for ‘personal reasons’. Lay returned to the role of CEO, attempting to reassure investors. However, the Chief Executive of a major company leaving with no notice was practically unheard of, unless the company was in serious trouble. Analysts also noted that prior to leaving, Skilling had sold over $30 million of his own stock in Enron, amplifying concerns. The share price continued to fall.

Amidst all this, strain on the Raptors was building. As they had to be owned at least partially by external firms, Enron couldn’t pump more debt into them without first securing some additional funding from those investment and equity firms. However, with Enron’s reputation in a nosedive, nobody was willing to help them. One by one, the Raptors began to fold, unable to continue to portray themselves as legitimate firms.

In October, the company finally came clean, admitting that from 1997-2000 it had overstated profits by 23% and underreported its’ liabilities. Fastow was ousted as CFO by the board of directors, and the share prices began to nosedive. Enron’s credit rating was downgraded, and a proposed buyout of Enron by energy giant Dynergy broke down as the extent of Enron’s financial difficulties became apparent. On November 8th Enron retroactively revised its’ earnings from 1997-2000 even further downwards, and on November 29th, its’ credit rating was downgraded to junk status.

On December 1st, 2001, with all other options exhausted, Enron filed for bankruptcy. One of the largest corporate darlings of America finally collapsed.

Lessons learnt?

The ‘Enron scandal’, as it was later known, laid bare the potential for companies to breeze by on reputation alone under the regulations of the time. In 2002, congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley act, subjecting firms to tighter accounting standards and more thorough audits to ensure transparency of all publicly-traded companies. By no means did this prevent companies from going down, or even prevent fraud from occurring – in the world of corporate law, bad actors always have, and likely always will try to find loopholes. What it did achieve, however, was make hiding debts and exaggerating profits a significantly more difficult endeavour. But perhaps more importantly, it gave a much-needed warning to those institutions that had been unwittingly complicit in Enron’s debt-shuffling antics: no matter how big the name or how alluring the potential returns, due diligence is key.

The scandal also reinforced important lessons for business leaders: Obsessive focus on share prices, rather than the long-term health of the business, can lead executives down a dark path to illegality. Even during crises, remaining ethical when tackling challenging situations is key – in the modern world, with investigative journalism and troves of open-source information, no large company should ever hope to hide assets on the scale of Enron again. Instead, they would do well to learn from Enron’s motto. Rather than scramble to hide poor performance in the hopes of placating investors, they should recognise their difficulties, and simply ‘ask why’.

- Key definitions:

- Dotcom Bubble: A period in time in the late 1990s when excessive investor optimism led to ‘dotcom stocks’ of tech-heavy firms, such as Amazon and Apply to become significantly overvalued. When the bubble ‘burst’, tech-related stocks nosedived in value

- Index: A tool used to measure the collective performance of a number of assets. For example, if Company A and Company B were added to the ‘alphabet index’, which started at 100 points, and Company A was valued at $80, and company B was valued at $20, and then Company B’s value increased to $90, whilst company A’s value nosedived to $5, the ‘alphabet index’ would fall to 95 points as a whole, reflecting the performance of all companies registered. Therefore, Indexes that contain big companies from a sector, such as the NASDAQ (a tech-heavy index), can give a good overview of the performance of the sector as a whole.

- Commodity: any interchangeable good that can be bought or sold. For example, gold: an ingot of gold that weighs one kilo has the same value as any other one kilo ingot of gold, and it can be bought or sold at negotiable prices on markets.

- Junk status: A name colloquially given to any company that has been issued credit rating of BB or lower. This indicates that there is a high risk of that company defaulting on its’ debts, but it will issue bonds at high interest rates to try to compensate investors for the increased risk.

- SEC: Securities and Exchanges Commission – a US government institution that is the main regulator of American securities markets.

NOTE: I’m aware that this article greatly simplifies and omits a number of details about Enron, including their forays into the broadband business, the trials of those responsible for the scandal, and the devastation that the collapse wrought on over 20,000 Enron employees. However, this article is already the longest that I’ve written by far. If there’s sufficient interest, I’d love to publish another, giving more detail about the facets of Enron that I haven’t yet covered. Let me know – I appreciate your feedback, and thanks for reading! – Alex

Leave a comment