As was discussed in the previous post, the Wall Street Crash was the economic shock that spelt the death of the gold standard, and led to the rise of fiat currency. With this, economies now had the power to inject additional money into their markets without increasing gold reserves. However, this came with its’ own risks: With the freedom to regulate and control currencies also came the responsibility of ensuring that confidence in them was maintained. During the days of the gold standard, the values of currencies were linked to the relatively stable value of gold, leaving relatively little room for inflation or deflation except by governments adjusting the exchange rate of gold for currency on a case-by-case basis. However, once the gold standard had been weakened to the point of ineffectiveness, major currencies were significantly more exposed to value fluctuations.

Take, for example, the British Pound. As we can see in this graph, from 1850 to 1914, when the pound was on the gold standard, although there are changes in the value of the pound in individual years, periods of inflation and deflation are relatively interspersed, resulting in very little change to the long-term value of the pound. Average year-on-year inflation from 1850 to 1914 averaged 0.24%. If we compare this period to inflation from 1945-2020, after the pound came off the gold standard in 1931, we see a vastly different picture. Excluding the years of the Great Depression and the second world war, we see that inflation during this period averaged 6.08% year-on-year, with positive inflation being recorded every year with the exception of 2009, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Inflation has become the new normal.

This is because moderate inflation actually encourages investment, consumer spending and economic growth. If the value of money depreciates year-on-year when not in use, then consumers are incentivised to spend their money sooner rather than later, to maximise the items that their money can buy. Similarly, investors are encouraged to make investments in businesses, putting capital into the markets, in the hopes of their assets appreciating faster than the rate of inflation. As such, a positive, stable inflation rate is a characteristic of stable economic growth, stimulating spending and investment. This has the potential to become a virtuous cycle: moderate inflation drives slight increases to consumer spending, which in turn, drives further slight inflation. By extension, negative inflation rates, or deflation, encourage savings at the expense of consumer spending and investment, meaning that an economy in deflation is significantly more sluggish, with worse growth prospects than one experiencing moderate inflation. An economy in deflation is therefore a serious cause for concern for potential investors and connected markets, something that we can see today with China: A few days ago, it announced that its’ economy had slid into deflation owing to sluggish consumer spending, unnerving analysts and would-be investors because of the implications that deflation has on prospects of near-term economic growth.

That’s not to say that high inflation rates are desirable in and of themselves. During periods of excessive inflation (for the purposes of this article, let’s say anything in excess of 5%, though ‘ideal’ inflation rates in reality may differ between economies), overly high inflation erodes even short and medium-term savings. This leaves consumers either unsure of making, or unable to make significant new purchases, lowering standards of living. Additionally, the economic uncertainty inherent with high inflation damages investor confidence, as they worry about the stability of businesses in a high-inflation environment. High inflation also redistributes wealth: employees with set wages may be able to negotiate for wage increases in line with inflation, but at times they are unable to, leading to a fall in their purchasing power. Similarly, savers with high liquidity suffer as their money loses value, whilst those who hold assets such as property see their assets retain, or even appreciate in value in real terms.

Therefore, as deflation hinders economic growth, and excessive inflation is a catalyst for economic instability, governments and central banks aim to keep inflation low – the current target set by the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and Bank of England are at 2%. However, with internal and external stressors on the economy constantly pushing the inflation rate upwards and downwards, external action is often needed in order to push inflation up, or more recently, to pull it down. This can take many forms, each with its’ own wider economic (and political) ramifications. Some of the main weapons in the economic arsenals of governments and central banks are as follows:

Altering bank interest rates

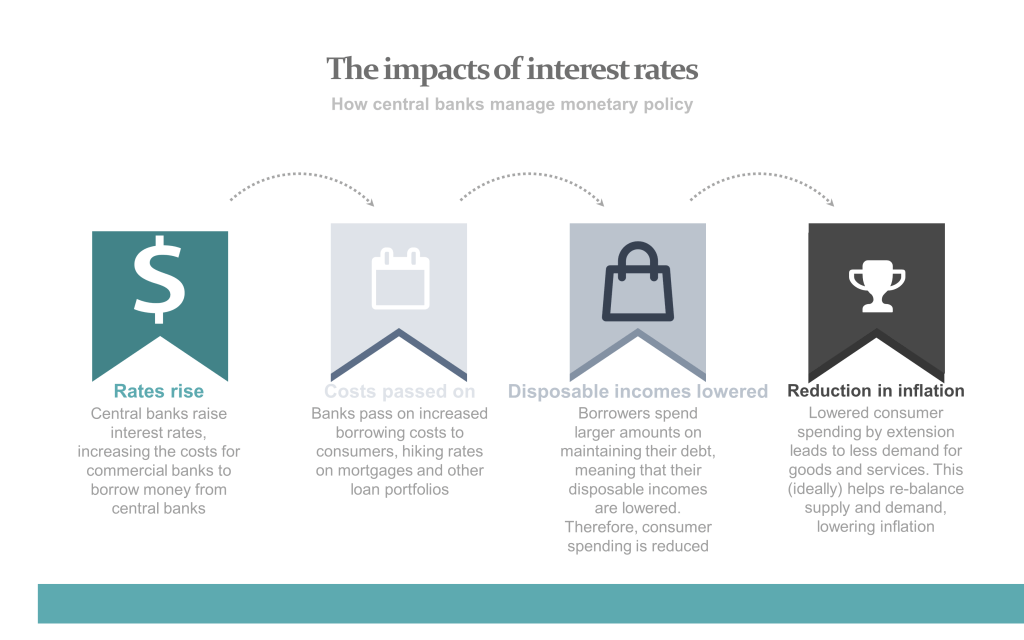

Raising and lowering interest rates: Perhaps one of the most often-used tools in monetary policy, central banks adjust their interest rates. That is, they alter the interest rates that they provide when lending their funds to commercial banks (known as the ‘bank rate’). This causes banks to alter their own lending rates in turn, changing the disposable incomes of borrowers. This modifies their disposable income, in turn changing the consumer demand for goods, which impacts inflation. Below we look at the impact of interest rate increases on inflation. Decreases to the interest rate would have the opposite effects.

However, this policy has some shortfalls. raises interest rates only reduces the disposable income of those who have significant debts. Therefore, the policy disproportionately impacts mortgage-holders, whilst actually benefiting savers. Additionally, higher interest rates limit the appetite of consumers to borrow money, as well as reducing the likelihood that consumers will be able to repay loans in full. Therefore, prolonged periods of heightened interest rates result in significant redistribution of wealth, lowering of living standards of debtors and mortgage holders, and an increase in the rate of defaults. Nevertheless, interest rates have a significant impact on the economy as a whole, and they are usually regulated by central banks rather than elected governments, and as such are controlled with the sole goal of economic regulation rather than gaining voter approval. Therefore, despite their drawbacks, interest rates are one of the most widely-used tools in the battle to tame inflation today.

Quantitative easing and tightening

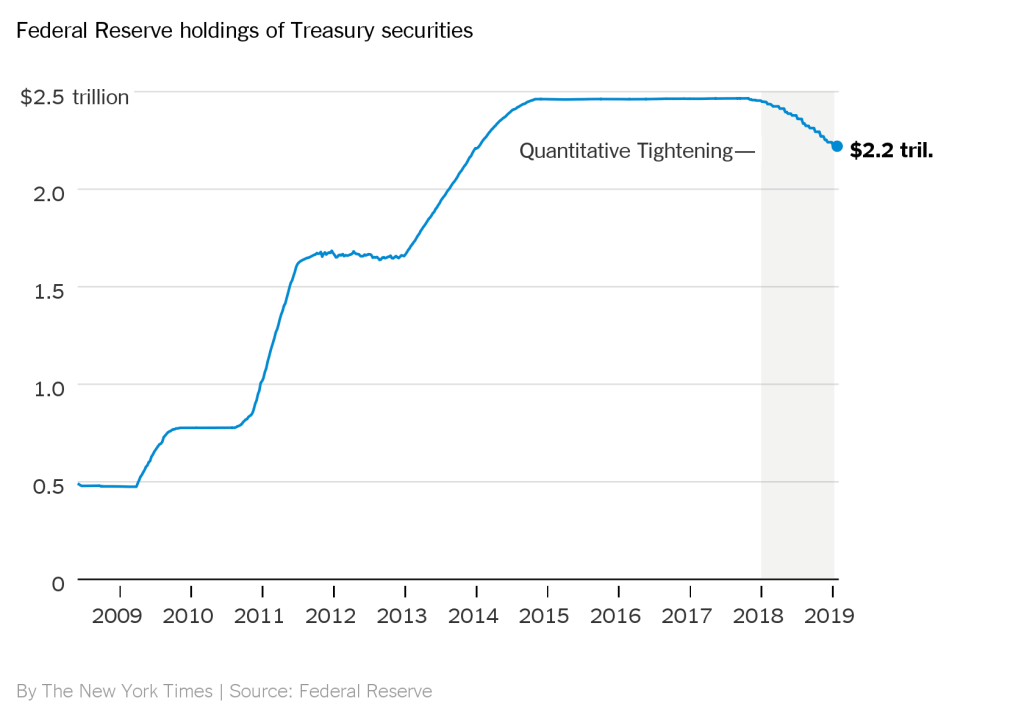

A newer strategy, which became available to central banks across the world is that of ‘Quantitative adjustment’ The premise behind this is that, when an economy is in a period of recession (as most economies in 2008 were), central banks can stimulate economic growth and reduce deflation, by directly purchasing securities such as government bonds. By purchasing assets, those assets are removed from the market and money is injected into the economy, stimulating economic growth and decreasing inflation. This is called quantitative easing.

Therefore, quantitative tightening consists of a selling off of accrued securities by central banks. This results in those securities entering the economy, and liquid cash leaving it. As there is now less money in the economy, and more assets, the rate of inflation decreases.

However, once again, quantitative easing and tightening have drawbacks and unintended consequences. Firstly, quantitative adjustments disproportionately impact pre-existing holders of securities, as the higher or lower demands for securities disproportionately impacts their values. Additionally, once implemented, quantitative easing is difficult to ‘unwind’, or reverse. Central banks must gradually sell off their securities, making sure not to sell off too much at a time, to ensure that the economy is unbalanced. On the flip side, Quantitative tightening is inherently limited by the amount of securities that a central bank holds – banks can only sell off as much securities as they own, and once those securities are exhausted, quantitative tightening cannot continue As such, it is not a sustainable long-term strategy to control inflation.

Another serious flaw with quantitative tightening is that it relies on the inherent stability of government bonds. If the government is in danger of accumulating an unsustainable level of debt, a central bank may be forced to undertake an emergency bond-buying program, which by removing government bonds from the market, stabilises borrowing costs at the expense of increasing inflation. We saw this during the September 2022 ‘mini budget’ of the UK. Proposed unfunded tax cuts were set to significantly increase the deficit, on top of debt which had already been accumulated during the earlier pandemic. In response, the Bank of England was forced to buy £65 billion worth of bonds to restore confidence in the pound. This came at a time when the inflation rate was already at 13%, fuelling further inflation when it was least needed in order to restore confidence in the pound.

Changing government spending and taxes

The methods discussed previously are the remit of central banks. However, elected governments have the potential to alter the rate of inflation by changing their spending decisions. When a government raises more money in revenue through taxation and other sources of income than it spends on public services and administration, it is in surplus. The government is effectively taking money out of the economy and storing it in the treasury, reducing the monetary supply. This has a deflationary effect, as there is less money in the system. Conversely, when a government spends more money than it brings in, it runs a deficit. The government is then effectively adding money into the economy from the treasury year-on-year, either through spending reserves or issuing new debt. This has an inflationary effect, as there is now more money in the economy than there would otherwise have been.

However, regulating inflation through government spending and taxation is rare. This is because governments come to power, and retain power, based on the approval (or at the very least, indifference) of their populations. Funding popular government programmes are expensive, whilst raising taxes, even on the highest brackets, tends to be a vote-losing strategy. The aim of governments is to stay in power, and for that purpose taming inflation is a single (important) factor out of several. For this reason, governments often rely on central banks taking the necessary measures to control inflation, whilst themselves focusing on treating the symptoms of inflation, and attempting to remain popular.

There is no silver bullet

Ultimately, inflation is not something that can be magicked away by cure-all solutions. Each method to lower inflation has its’ own setbacks, dampening economic growth, and targeting certain people over others. Similarly, methods aimed at raising inflation, or stimulating economic growth benefit disproportionately benefit certain people, and run the risk of fuelling long-term high inflation. Ultimately, when walking the tightrope of monetary policy, buffeted by external factors and unexpected pressures, central banks and governments must maintain a delicate balancing act.

- Definitions:

- Securities: By its’ broadest definition, any financial instrument that holds a monetary value and is used to raise capital This can include government and corporate bonds, and shares in private companies.

Thank you so much for reading through! I hope you found this article informative. I appreciate any and all feedback, constructive criticism, and advice, so if you have ideas for future posts, or you think I could have done something better when writing this article, don’t hesitate to leave a comment! -Alex

Leave a comment